One of the ideas behind ShopHouse is “healthy”. Things like indoor air quality are important to us. We’re spending a lot of time on HVAC, but even the materials in the overall construction are important decisions and opportunities to make sure our indoor environment is the best if can be, as well as making sure that we at least try to choose environmentally decent materials.

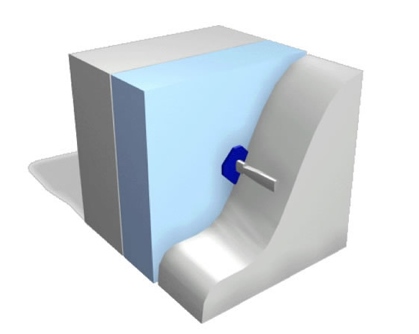

Additionally, we’re incorporating a split footing design, where 2 halves of the footing are thermally isolated from on another, and also insulated from the ground (more on THAT project shortly). So – we needed a source for 4″ xps foam to get the R values we needed AND it needed to have sufficient compressive strength to hold up the house (minor detail). The search started with the usual suspects – Dow, and other companies that seem to be more chemical that insulation…

And… then we find out that all the foam insulation that appears to be available in the US contains HBCD (Hexabromocyclododecane – there will be a spelling quiz later – so pay attention) – a bio accumulating chemical that is banned in Europe and in the process of being phased out globally. It’s a flame retardant and blowing agent. Read the link for a more detailed discussion on why this is bad stuff.

Why would we want THAT all in the ground around our house and under the slab? It doesn’t need to be flame retardant, and we’re anti – nasty chemical. So intrepid husband starts the search for happy foam to make our footings.

The US companies’ answer for removing HBCD is just to find a better chemical and make everything flame retardant. Sigh.

Enter – FINNFOAM!

In northern Europe, apparently what we’re doing isn’t all that odd, and Finnfoam complies with the stricter chemical regulations of the EU.

So we’re now experts in importing Finnish Foam by the container. Interestingly enough the cost was equal to the “blue foam” even including ocean freight. We paid for the foam to be delivered and then unloaded it all into our trailer and basement.

Another round of my personal slave labor. That was an entire 40 foot – high cube container…..

Now – on to the form making!

I look at conventional 2×4 construction as “lowest common denominator” construction – while it is cost effective I find it to be incredibly wasteful and sloppy. It also has a fundamental problem that we needed to avoid to achieve our “cooler” concept of thermally isolating the inside of the house from the outside as much as possible. Every 2×4 creates thermal paths between inside and outside surfaces, thus creating thousands of holes in the thermally isolated “bucket” that we are trying to achieve.

I look at conventional 2×4 construction as “lowest common denominator” construction – while it is cost effective I find it to be incredibly wasteful and sloppy. It also has a fundamental problem that we needed to avoid to achieve our “cooler” concept of thermally isolating the inside of the house from the outside as much as possible. Every 2×4 creates thermal paths between inside and outside surfaces, thus creating thousands of holes in the thermally isolated “bucket” that we are trying to achieve.